It’s possible to mistake Ivy Creek Natural Area & Historic River View Farm, located off Earlysville Road in Albemarle County, for simply a nice place to take a hike, with gentle hills, thriving wildlife, and views of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Lisa Shutt, an Associate Professor in UVA’s Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies, had taken several walks in the area before she took an interest in a towering white barn near the trailhead.

“I didn’t know the history of the barn, I didn’t know the history of the lands that Ivy Creek Natural Area is on,” she said. Once she found out that history, she couldn’t stop thinking about it. Her curiosity about the place led to a partnership with UVA Library, which, for the past year, has been working in various ways to help resurface and preserve information about the area, originally known as just River View Farm.

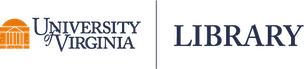

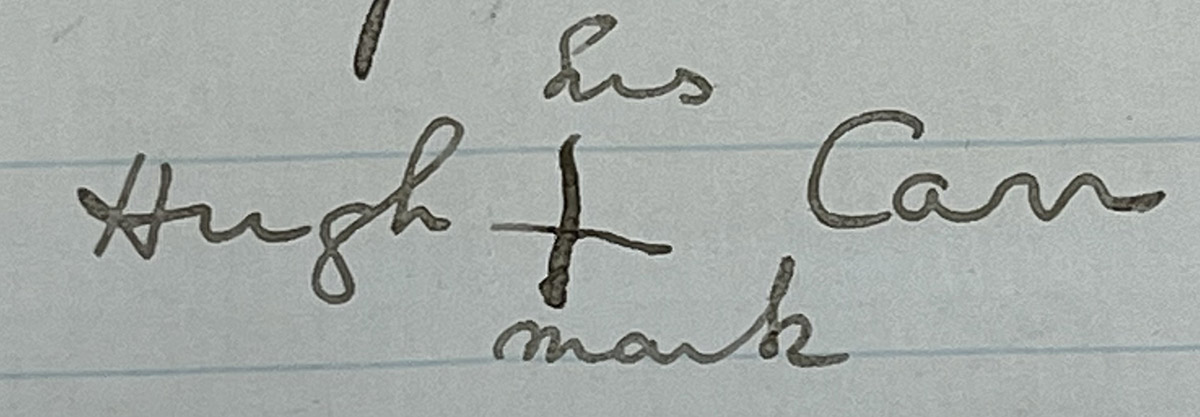

In 1870, Hugh Carr, a recently emancipated Black farmer, paid $100 for 58 acres of land near the intersection of Ivy Creek and the Rivanna River. Carr continued to accumulate land, growing the property to nearly 125 acres. He built an I-House farmhouse and multiple outbuildings, and raised seven children there with his wife, Texie Mae Hawkins. Their eldest daughter, Mary, inherited the farm and served as a prominent educator in the African American community, eventually becoming principal of Albemarle Training School — one of the only schools in the area where Black children could continue their education beyond seventh grade. She added to the farm over the years by buying adjacent pieces of land, which her siblings and others had owned. Her husband, Conly Greer, was the first Black agricultural extension agent in Albemarle County. He traveled the county by horseback to train other Black farmers in cutting-edge agricultural methods. From 1937-38 he built the large frame demonstration barn that caught Lisa Shutt’s attention so many years later.

“I became fascinated by this place and wanted to preserve and share the legacy of this incredible family, especially with UVA students,” Shutt said. “Most of the people I come across who are deeply invested in the preservation of non-UVA local histories tend to be community members. I want our students to be just as invested in local histories.”

While the City of Charlottesville and Albemarle County own the land and maintain the buildings at Ivy Creek Natural Area & Historic River View Farm, the Ivy Creek Foundation helped get the property listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the past couple of years, Susie Farmer, the Director of Education for the Ivy Creek Foundation, has worked with UVA’s Special Collections Library, where many documents relating to the family and farm are held.

Shutt reached out to Farmer and local historian Alice Cannon to further research the work and teachings of the Carr and Greer families. This past spring, with the permission and support of the Ivy Creek Foundation, including their Descendants’ Committee, Shutt taught a UVA African American Studies seminar, “Engaging Local Histories: River View Farm.” The class brought undergraduate students to the land, as well as to Special Collections. “I wanted students to think about what Black communities and Black individuals had to do in order to be successful in time periods where that was made extremely difficult by white power structures,” Shutt said.

“Successful research and preservation is a wildly collaborative effort that calls upon a variety of specialized skills for advancement: genealogy, 3D scanning, archival maintenance, navigation, cataloging, and even re-cataloging,” said Librarian for African American & African Studies Katrina Spencer, who helped Shutt’s students with their research. “The work on River View Farm with local community members is a great example of that.”

History made real

Students in Shutt’s class hiked the land, learning which areas were used for farming, and explored the barn’s interior. They visited local food scholar Leni Sorensen on her farmstead in Crozet, where, in the tradition of Mary Carr Greer’s food preservation classes, Sorensen taught them how to make and preserve strawberry jam. The students were trained to be barn docents, giving them the ability to lead tours of the entire farm. And Shutt reached out to Spencer, who is also the Library’s subject liaison to the Woodson Institute, to help guide her students through the Carr family papers in Special Collections.

Spencer prepared an instructional session for Shutt’s students and enlisted Jean Cooper, the Library’s Principal Cataloger and Genealogical Resources Specialist, to assist. The two tailored the session, held in Clemons Library, to the various topics on which students were focusing: some were researching Black education, others were delving into Black land ownership. The librarians gave an overview of how to identify primary sources, how to search databases and access Special Collections, and how to interpret census data, with a deep dive into genealogy, a specialty of Cooper’s.

“Charlottesville is the kind of place that grabs you and won’t let you go; it’s a fascinating place,” Cooper said about conducting genealogical research. “African American genealogy is especially fascinating because it’s so hard. There’s not a whole lot of written evidence … and so you have to figure out how to get there.”

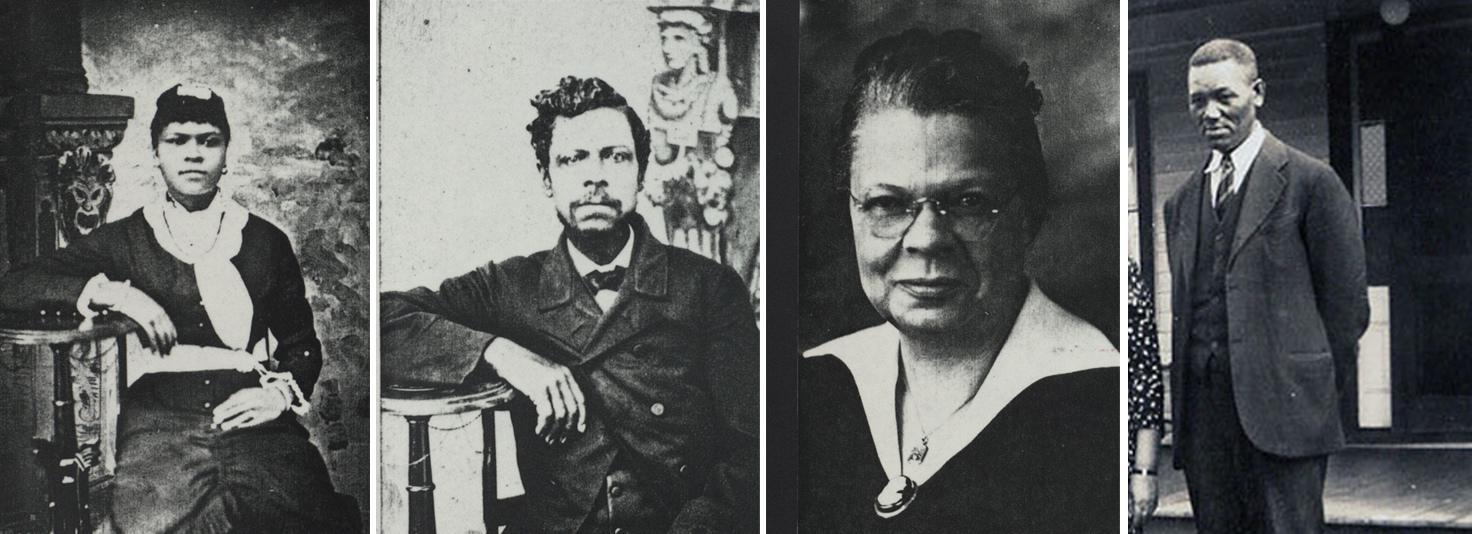

With training from Cooper and Spencer, the students were ready to visit Special Collections a week later to explore three boxes of Carr/Greer papers. “When the students got to Special Collections, they just kind of were in awe,” Shutt said. “I would call it almost a spiritual experience to be able to put our hands and eyes on these documents that were once held by members of this family: a little cookbook, the original contract where Hugh Carr made his mark to pay for the land, academic papers written by Mary Carr Greer when she studied at the Piedmont Industrial Institute.”

Shutt said the students returned to Special Collections without her several times, sending her photos of things they found. The primary documents they analyzed became source material for 20-page research papers each student wrote at the end of the semester. “I think sometimes when students are examining history, it can seem like a fairy tale to them, like they’re watching a movie or reading a novel; it’s so removed from them,” Shutt said. But when they either go to River View Farm or to Special Collections, history is made real.”

Taylor Whirley, a rising third-year student who took Shutt’s class, agreed. “I became engrossed within the history of a family that I had never met and am not a part of, but I quickly developed a desire to ensure that their stories were told within the UVA community,” she said. “Through this class, I learned more about Charlottesville and Albemarle County history than ever before, which was an incredibly eye-opening experience in general.”

Reparative work at the Library

When Shutt reached out to Spencer for help, the request led not only to a successful instruction session, but also to some necessary updates in the Library’s records.

“I saw the term ‘River View Farm’ for the first time when Lisa got in touch with me,” Spencer said. “I didn’t know what it was. And I knew that if I was going to teach about it, I had to start doing some digging.” She was surprised to find scant information about the family members in the Library’s catalog when she began searching for it. “Our River View Farm entries didn’t reference Hugh Carr, or Mary Carr Greer, or that family. And I thought, ‘Well, shouldn’t these go together, if these were the people who owned this property and developed it?’”

Spencer approached Ellen Welch, a Library Manuscripts and Archives Processor, for help with this issue. “Part of my work is responding to suggestions for improvements in describing our collections,” Welch said. “The description for the Ivy Creek Natural Area papers was so minimal that the history of the Carr family was invisible to anyone searching our collections. With Katrina’s suggestion, I was able to bring the Carr family history into the description so that patrons can know more about this important family in Albemarle County during the 19th century.”

In March, Welch published a deeply researched post on the Special Collections blog, “Notes from Under Grounds” exploring the Carr/Greer family and the Library’s Papers of the Ivy Creek Foundation collections (MSS 10770 and MSS 10176). “As a longtime local resident, I had known about the Ivy Creek Natural Area but had no knowledge of Hugh Carr,” she wrote. “This is what makes reparative work so essential in libraries and historical repositories. It is exciting to shine a light on their remarkable lives, making them well known to our patrons today and in the future.”

3D cultural heritage data

While Welch was illuminating River View Farm history in the Library catalog, Will Rourk, the Library’s 3D Technologies Specialist with the Scholars’ Lab, was creating new primary source data about the site for historic preservation purposes, using high-tech equipment to do so.

With an academic background in architecture and architectural history, Rourk is an expert in cultural heritage preservation using 3D data. Equipped with laser scanners, aerial drones, and photogrammetric technologies, Rourk teaches architectural history students to collect, process, preserve, and distribute 3D data of historic objects, buildings, and sites, including the Rotunda Dome, archaeological artifacts at Monticello, and the Pine Grove School in Cumberland, Virginia.

During the fall 2022 semester, Rourk’s students used laser scanning equipment to collect 3D data of the barn, the farmhouse, and surrounding landscape at River View Farm. “In all we collected 55 individual scan datasets of the barn and 123 datasets for the house and landscape,” he said. His students produced a thorough storymap website on their work. Late last month, Rourk uploaded all of the data about the barn and farmhouse to LibraData, UVA’s data repository, hosted by the Library.

“Once the 3D data is up in the Library, then it’s accessible to the scholarly community,” Rourk said. The data has a variety of uses, including historic structure reports for architecture firms, 3D printing of artifact replicas, or even for the immersive virtual reality spaces in the Library’s Robertson Media Center. “We have a ton of this data running in the virtual reality lab in Clemons,” Rourk said. “You can virtually visit the Pine Grove School, cabins for the formerly enslaved, as well as the [now demolished] U-Hall arena.”

Rourk is planning on loading the River View Farm data onto the VR stations in Clemons for virtual explorations this summer. The data is also being used to help preservation efforts of River View Farm. Rourk is working closely with Jody Lahendro, who was a preservation architect at UVA for 16 years and now, in retirement, serves as a board member of the Ivy Creek Foundation. The 3D data from Rourk and his students will be crucial to Lahendro’s current volunteer work assisting Albemarle County Parks & Recreation in developing a historic structure report for River View Farm.

“All these people in the historic preservation community that I work with are just doing amazing, interesting work. And I am propelled by their eagerness to do good,” Rourk said. “I feel like the Library does good because we help people who do good. And this is one small way that I can do that.”

To take a tour of River View Farm or to learn about other educational events and scheduled hikes on the land, visit the Ivy Creek Foundation website.